(Editor’s note: Summer is the time many people move into new towns, including many moving into Los Banos, Dos Palos, Firebaugh and Santa Nella. For people new to the area, the Garden Guru provides an introduction to the native growth of the Westside.)

Los Banos and the rest of the Westside of the Central Valley have a wide-ranging biodiversity of native plant species, trees and grasses. It’s a unique area compared to other urbanized areas within California. Why is this? The answer is the weather and soil.

Here is a brief description of the native flora of our Westside in answer to numerous discussions, stories and arguments I have heard, directly and indirectly.

While I know my information and studies are accurate, many might question my knowledge and go as far as settling many moot questions in the field of native plant identification and habitat.

Our winters are cool but with very little rain, averaging 10 inches yearly. Our soil is high in alkalinity and salinity. With little rain, hot and dry summers, wind and alkaline soil, we are limited in what we can grow without plants, trees and grass turning yellow and stunted.

The flatlands of our Westside are basically alkaline sink environments, which are salty basin landforms. In the depressions, rainwater drains to the basin and collects due to a hard layer of clay or caliche and ponds up. When the water evaporates, it leaves increasing amounts of salt and minerals.

Plants that tolerate extreme salt concentrations are known as halophytes. Some familiar alkaline sink flora you can identify here include iodine bush, bush seepweed, desert saltgrass, alkaliweed and heath.

The outermost regions of our flatlands are our wetland marshes, which have entirely different environments and ecosystems supported by standing fresh water. Here, you will see riparian stands of Fremont cottonwood, sandbar, red and arroyo willows, native sedges, bulrushes and cattails.

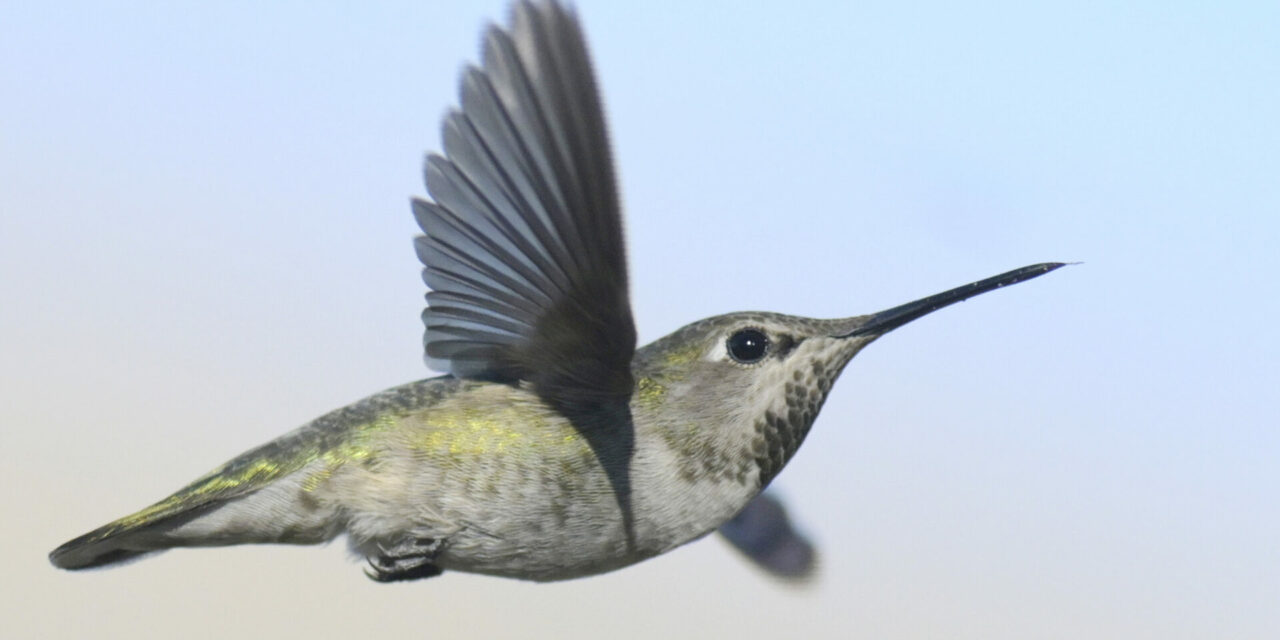

Our wetlands not only support an entirely separate flora but support 200 bird species, pond turtles, beavers, muskrats and various mammals.

To our west is the Diablo Range, where the flora consists of oak woodland, chaparral and grassland. The indigenous soil is also completely different from the valley floor. Essentially, it has a chaotic mixture of intensely sheared sandstone, shale, chert and embedded basalt.

The oak woodland is the overstory dominated and canopy closure of evergreen and deciduous species, such as coastal live oak and blue oak. Although the community is named for the dominance of oak trees, the understory vegetation is often diverse, including many species of grasses, sedges, forbs, ferns, legumes and the Ribes genus.

The chaparral and scrub biome grows on the Diablo Range’s hot, windy, dry western slopes. Many times, you can find the chaparral in pure stands in and around boulder outcroppings. Much of the chaparral found in our range consists of California and white sage, coyote brush, toyon and manzanita.

During the time of our first settlers, much of our native grassland consisted of native bunchgrass, brome and oat grass. Good examples are located on the sloping hillsides of Pacheco Pass and near Interstate 5.

For generations to come, protecting and saving our California native flora is crucial. Unfortunately, California’s rich diversity faces many threats, including urban, natural resource and agricultural development, contributing to habitat destruction and fragmentation, nonnative species, changing fire regimes and climate change.

Much of our native flora would benefit from increased monitoring and research. Recognize threatened or endangered species and begin storing through represented in regional seed banks.

Mark Koehler of Los Banos is an arborist and master gardener who has degrees in landscape architecture and landscape horticulture from UC Berkeley and Northeastern University. Please send any questions or comments to markgardenguru@gmail.com.