BY MATT JOHANSON

Special to the Express

Women’s History Month makes a good time to reflect upon female outdoor achievements. In Yosemite, for instance, Clare Marie Hodges became the National Park Service’s first female ranger, Lynn Hill made the first free ascent of The Nose of El Capitan, and Heather “Anish” Anderson hiked through to a Pacific Crest Trail speed record. Yet none of them would have had such opportunities without the efforts of another remarkable woman.

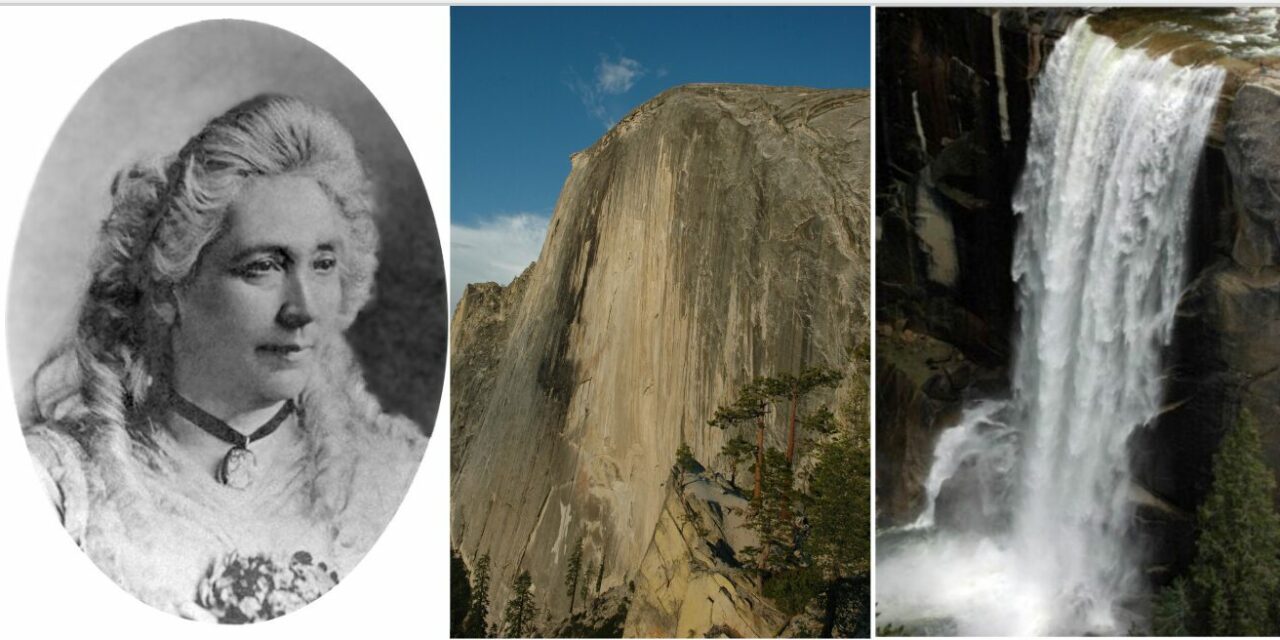

Before national parks existed, Jessie Benton Frémont (1824-1902) mobilized influential people behind a then-radical cause: preserving Yosemite for the nation’s future.

“This lovely valley is rimmed about by ranges of mountains rising from green foothills to the dark Sierra, snowcrowned,” she wrote. “So few people have seen the grand scenery of the Yo Semite that it needs a little explaining.”

Frémont convinced politicians, writers and naturalists to join her effort, and then traveled to Washington in 1864 armed with Yosemite’s first photos. Thanks in no small part to Frémont, President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, the first such land preserve in the nation’s history.

Men who supported Fremont’s Yosemite fight have mountains named in their honor. No such geography bears the name of Frémont, an author and abolitionist, though her modern-day admirers have tried to change that, and California Outdoors Hall of Fame inducted her last year.

“If not for what she did behind the scene, during an age when women did not have the vote or any voice in public life, would there be a Yosemite National Park today?” asked historian Craig MacDonald.

There would not, said conservationist Galen Clark.

“Yosemite would not have been saved if it hadn’t been for the efforts of Jessie,” said Yosemite’s first official guardian.

In honor of Women’s History Month, let us recognize more California women who selflessly saved and shared the outdoors.

Anyone who’s hiked in the High Sierra or climbed Mount Whitney should thank Susan Thew. She journeyed hundreds of miles through these mountains, producing a 68-page book which she submitted to Congress in 1926. Lawmakers had rejected several earlier proposals, but Thew’s photography coaxed them to extend Sequoia National Park’s boundary to the Sierra crest. “I know of no better place than the wild loveliness of some chosen spot in the High Sierra,” Thew wrote.

Though she hailed from Mississippi, Minerva Hoyt loved camping in the desert. “During nights in the open, lying in a snug sleeping-bag, I soon learned the charm of a Joshua Forest,” she wrote. “This desert possessed me, and I constantly wished that I might find some way to preserve its natural beauty.” Hoyt campaigned tirelessly to preserve California’s deserts, convincing President Franklin Roosevelt to create Joshua Tree National Monument in 1936. A half century later, Senator Dianne Feinstein convinced Congress to make it a national park and enlarge it. Mexican President Pascual Rubio named Hoyt “the Apostle of the Cacti.” The U.S. government honored her as well, naming Mount Minerva Hoyt after her.

Born in 1910, Sada Sutcliffe Coe Robinson grew up on her father’s ranch in Santa Clara County’s foothills. “The world I grew to know was the mountains and ranges!” she wrote. “Wilderness and long-horned cattle! My cradle was my father’s strong arms and a blanket across the front of his saddle.” After her father died in 1943, Robinson donated the 12,000-acre ranch for a park honoring his memory. Henry W. Coe State Park formed in 1958 and since then has grown to 87,000 acres, the largest state park in Northern California. “May these quiet hills bring peace to the souls of those who are seeking,” she expressed.

Following a long career in social justice causes, Lupe Anguiano led a successful effort to prevent construction of a liquified natural gas terminal off the coast of Ventura County. Anguiano founded an environmental group called Stewards of the Earth in Oxnard, volunteered for the California Coastal Protection Network, and campaigned against air pollution, fracking and pesticides. She won honors from the California Assembly, National Women’s History Project and Women’s Economic Ventures, and is still going strong in her 90s.

Lisa Maloff, the “Angel of Tahoe,” supported parks and wildlife care as she donated more than $40 million to countless causes and charities in the Lake Tahoe area. She died in 2022 at age 93. “Her presence and spirit will continue to be felt every day,” said South Lake Tahoe Mayor Devin Middlebrook.

Descended from Eastern Sierra Paiutes and Tule River Yokuts, Jolia Varela founded the nonprofit group Indigenous Women Hike. She led a group of mostly Paiute (they also call themselves Nüümü) women on a trek through their High Sierra ancestral lands in 2018. “It’s time to get our community out and nourish the connections that we have to the land to make us healthier,” Varela said.

To encourage more Black people to enjoy outdoor activities, Rue Mapp of Oakland created Outdoor Afro in 2009. The group has grown quickly with more than 100 volunteer leaders in 60 cities and some 60,000 participants. Mapp authored the book, “Nature Swagger: Stories and Visions of Black Joy in the Outdoors.” “Being outdoors is about people getting out and finding that healing for themselves,” Mapp said.

If you spend time outdoors during Women’s History Month (and you really should), take a moment to consider the women who improved your experience.

“Nature has been for me, for as long as I remember, a source of solace, inspiration, adventure, and delight; a home, a teacher, a companion,” wrote author Lorraine Anderson.

“My mom and my dad taught me the greatest gifts we have are our family, our health and the right to clean water and good land,” said environmental activist Erin Brockovich.

“Let us be the ancestors our descendants will thank,” said conservationist Winona LaDuke.