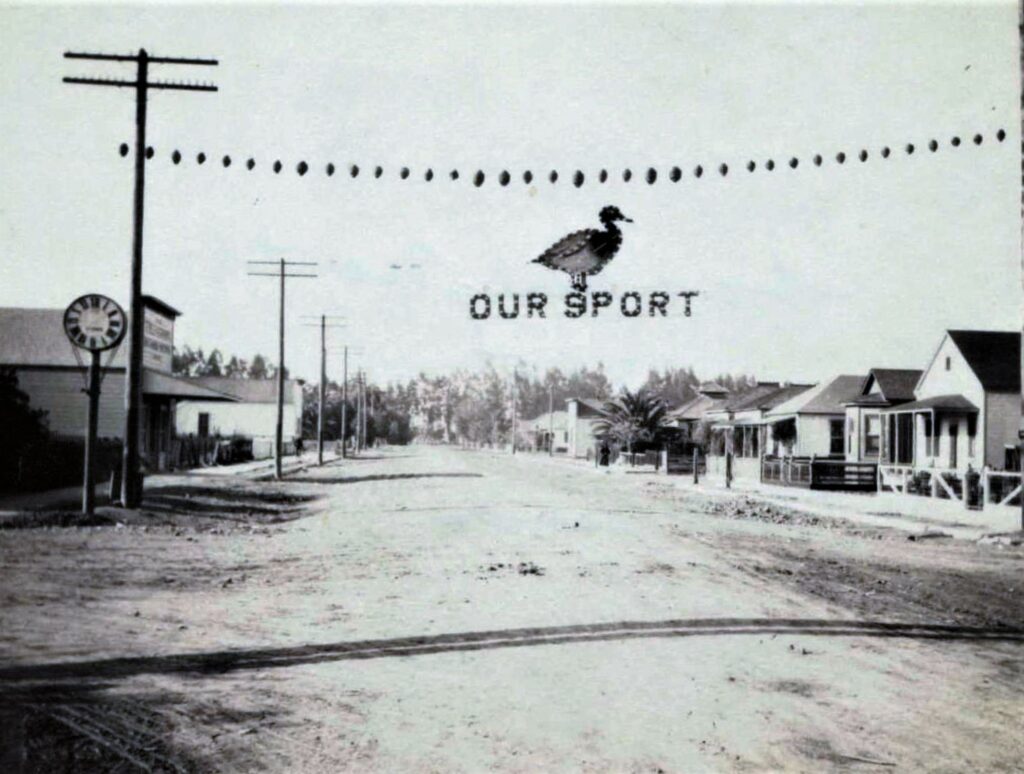

One of the things that makes Los Banos and the Greater Westside unique is our proximity to marshes and waterfowl habitat. This is complimented by being smack-dab in the middle of the Pacific Flyway, an airstream highway for migrating ducks and geese.

Our history is filled with legendary stories of blackened skies, market-hunting legends, game-wardens and notable enthusiasts including Bing Crosby and The Babe.

This is such an important part of us that when Los Banos was provided its first access to public electricity in 1911, we celebrated and commemorated it with an electronic “Our Sport” sign, featuring a lit-up illustration of a duck that was strung across the entryway to downtown Los Banos.

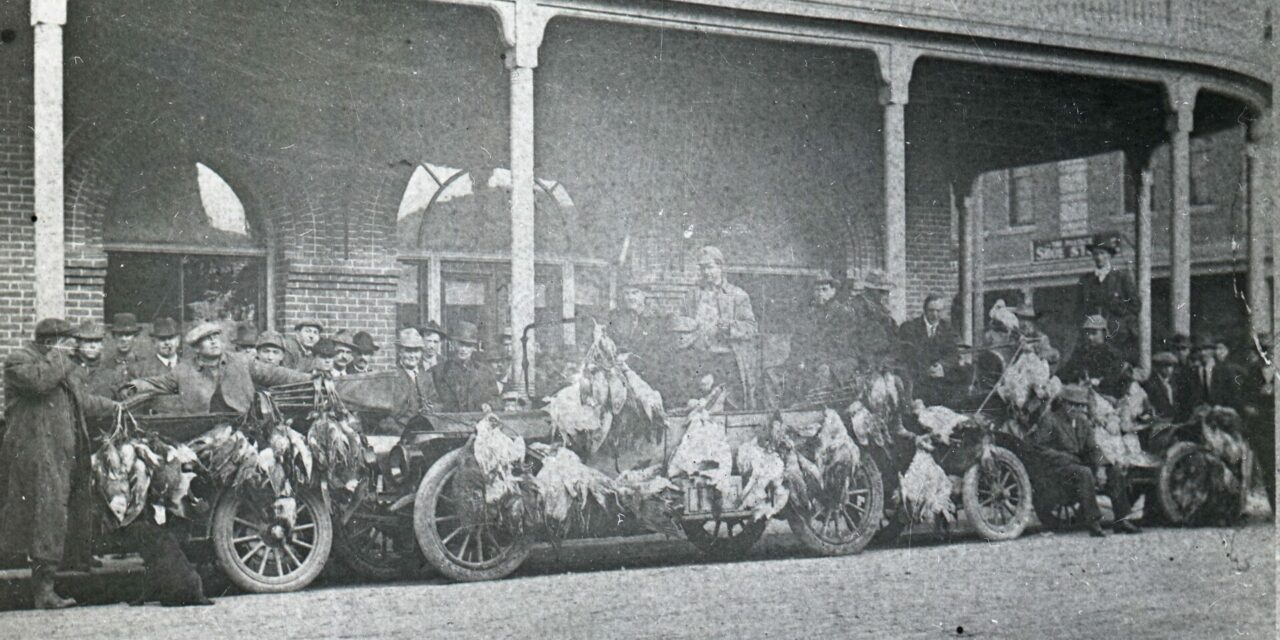

The westside had an abundance of wildlife including tule elk, waterfowl, antelope and even grizzly bears. Hunting was always an important part of our culture. This was enhanced by the coming of the railroad in 1889. The railroad provided hunters the opportunity to sell their game to San Francisco and beyond and it quickly became a significant part of the local economy.

From the unbridled early 1900s to the tumultuous 20s and 30s market hunting was a significant part of the culture and economy of the town. Market hunting became a convenient economic opportunity for the region. This became even more important during the 1920s depression years.

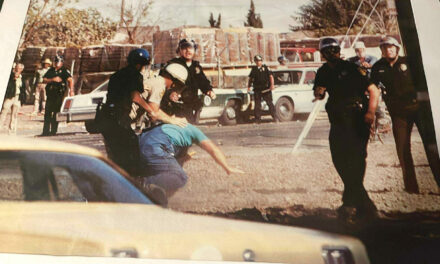

Federal agents were delegated in the mid-1930s to get a grip on market hunting. Los Banos was culprit number one in the federal government’s efforts to crack-down on the abuse. This crack-down is documented thoroughly and colorfully in a book written by Federal Agent Hugh Worcester, “Hunting the Lawless,” and provides us valuable insights of the events and culture of the time.

The town’s sympathetic leanings to the market hunters changed along with the federal intervention in the mid-1930s. Prior to that the market hunters were mythical and their prowess legendary, making them hero-like in the community. Even when caught, it was near impossible to get a conviction in the local courts with the local jurors. This changed, along with public perception, with federal convictions in federal courts.

Market hunting was at the end of its apex in 1936 when the notorious kingpin Howard “Bluejay” Blewett was arrested and convicted in federal court, along with a gang of nine supporters.

Blewett was known by the federal agents as “Dillinger No. 1 of Duck Bootleggers”. Blewett’s harsh sentence of 18 months at a Federal Road Camp in Arizona was a reality check and dissuaded further illegal hunting. As an interesting side note, while Blewett was serving his time he became enamored and studied the legal system. When released he pursued a legal career and ultimately became a judge.

Laws and regulations have evolved to preserve the remaining wetlands and waterfowl. The 240,000 acres of contiguous marshes and habitat in the region are now managed and regulated by an array of effective local, state and federal governmental agencies working in tandem with publicly owned duck clubs.

At least annually we are reminded of our wildlife heritage through the influx of hunters from all over the state. They can be seen at our hotels, grocery stores, restaurants and, last but not least, the bars. In more recent decades, birdwatchers and wildlife enthusiasts have discovered us as well.

As we wind-down on the 2022-23 waterfowl hunting season it’s fitting to remind ourselves of how fortunate we are to have this unique resource in our backyard, along with its history.

Welcome to “Our Sport”, welcome to our heritage/history, welcome to Los Banos and the Greater Westside.

(Photos and information for the article are from the archives of the Milliken Museum in Los Banos including Charles Sawyer’s book “Our Sport, Market Hunting”. The Milliken Museum is operated by the Milliken Museum Society, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 1pm – 4pm.).