My goal is to dazzle,” said interim finance director Brent Kuhn during the June 7 Los Banos city council meeting as he explained why he needed two more weeks to prepare the 2023-24 city budget.

When the budget was presented on June 21, city council member Deborah Lewis was not dazzled. She was dismayed.

“This is the first time in my 11 years on the council that we’ve not had a budget hearing,” said Lewis. “All government agencies have hearings about their budgets; every city has public hearings on budgets. It allows those elected to office to dig through it, to ask questions, to be educated about what’s in it before we make final decisions.”

Her first look at the 305-page document came just 72 hours before the June 21 meeting. With no council member other than Lewis asking questions, the city’s $110.1 million budget was presented and passed in 55 minutes on a 4-0 vote with Lewis abstaining.

Mayor Paul Llanez and councilmember Ken Lambert said the budget was structured to get things done. Llanez responded to Lewis’ objections about not having time to consider the package by saying, “I can reach out to staff at any time,” then asking, “does your email or phone not work?” inferring that Lewis had not reached out.

“I asked to see the (draft) several times,” Lewis said. “But there was never any comment from the mayor or the city manager when we had meetings. It was like I was speaking to air.”

Keeping Lewis in the dark was by design. Two sources within city government who fear retaliation if identified said manager Josh Pinheiro has ordered staff not to talk to any council members. But, said one, “we’re not to respond to one particular council member at all. That member (Lewis) has no weight with the city manager.”

Lewis was not alone in the dark. Several people at the June 21 council meeting complained they couldn’t find the city budget online or on paper.

“That, to me, was wrong,” said former councilmember Refugio Llamas, who has announced he will run for mayor in 2024. “It’s incredible, and it’s not how we operate in an open government.”

Search for “budget” on the city website and you will be taken to the budget landing page, where the 2022-23 budget is the most recent of nine provided – stretching back well into the era when Sonya Williams was finance director. The 2023-24 budget, assembled by interim finance director Kuhn and approved in June, is not there.

A city official told The Westside Express that the 2023-24 budget was “basically” the same document provided in the June 21 city council packet. The only way to find it without a link is to visit the city website, click on the News header then select City Council in the drop-down. Then click on the June 21 meeting and then click on “Agendas Packets” and scroll to it.

Budgets provide a narrative of city priorities and a blueprint for how cities will spend taxpayer dollars. Most cities take great care to incorporate both council and public priorities into annual budgets. For instance, the city of Merced conducts town-hall meetings where residents offer comments, outline their desires and bring up issues. In different meetings, department heads are consulted about what they need in the coming year – new equipment, staff, new projects, etc. – and what is needed to stay in step with the city’s strategic plan. All that information is coalesced into a budget.

Such coordination, in the words of one Los Banos employee, “keeps the city staff from operating aimlessly, reacting to the flavor of the day — whatever problem is popping up or is on the city manager’s mind.”

What were some of the priorities included in the most recent budget?

On page 225 is language allowing the city manager to transfer up to $200,000 between city accounts without council approval. All cities allow transfers, but for amounts far smaller – usually no more than $25,000 and often less.

On page 242 there’s $120,000 to purchase two new SUVs for city hall administrative staff.

On page 240 is language that makes most mid-tier managers at-will employees – meaning they can be fired by the city manager. This change was enacted by a 4-1 vote on Sept. 6, as the council changed the status of 13 city jobs.

There are good reasons to insist on rigorous budgeting of any city’s resources and accounting of its expenditures. In 2009, two Los Banos city employees were arrested and later imprisoned in separate incidents for embezzling a total of $2 million. The 2010-11 Merced County Civil Grand Jury investigated and recommended better handling of records, semi-annual audits and greater council follow-through.

Many public entities have weathered similar incidents, usually resulting in commitments to better adhere to public accounting procedures such as requiring all expenditures to be properly vetted, approved, documented through receipts then posted to proper budget categories ready for audit.

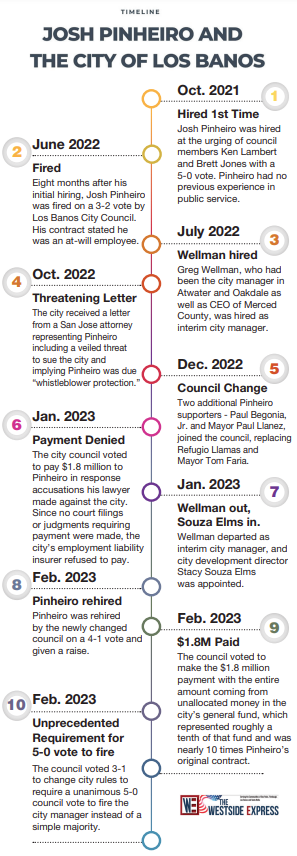

Unfamiliarity with many such rules – from city finance to municipal codes to reporting requirements — has contributed to the controversy surrounding the hiring, firing and rehiring of city manager Pinheiro and his performance. So have a host of other issues – including creation of 20 new city staff positions, burgeoning consent agendas that make city business less transparent, abandoned city projects, perceived irregularities in disbursal of federal COVID-relief funds and possible Brown Act violations.

Pinheiro did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Those who approve of Pinheiro’s performance point to newly painted buildings, street paving projects and anticipated pickleball courts. But others note that paint and pavement are upkeep for city property, and the pickleball courts have not been started. Other issues leave them more concerned.

Start with the plan, found in the 2023-24 budget, to add 20 new staff positions.

“I don’t know how we can afford it,” said Lewis. “The acting finance director (Kuhn) is saying (the budget) is basically the same as it was last year. But if it’s the same, how can we afford all these new positions?”

Others noted that employment costs don’t end with salary; cities must pay into ongoing retirement and healthcare funds.

Councilmembers like Jones and Lambert justified the new hires by saying previous councils had hoarded money, leaving the city understaffed.

Among those new hires would be the city’s first assistant city manager. Llanez justified that new position by saying the city had been without a manager for 26 days between Pinheiro’s firing and the hiring of interim city manager Greg Wellman in 2022.

Llamas sees it differently. “We were told Mr. Pinheiro has all these, these abilities, this incredible background and he’s a one-man show who can do it all. Now we’re being told that he can’t do it on his own, that he needs an assistant city manager.”

As for hoarding city funds, Llamas says that in 2022 the council “saw potential problems with interest rates, inflation and refinancing loans and the five-year forecasts. … We wanted to have reserves for any potential downturn.

“It’s not our money. We’re responsible for it, but it’s not ours,” said Llamas.

Merced County released its 2023-24 budget this week, with Supervisor Scott Silviera telling the Central Valley Journalism Collaborative that he expects to “feel the pinch” as sales tax revenues stagnate.

The California League of Cities conducts training to help cities “guard against becoming a Bell” – one of the most notorious corruption cases in state history resulting in the imprisonment of the city administrator and several members of its council and staff. In its anti-corruption training materials, the League says councilmembers must put “stewardship of public resources” at the center of decision-making while simultaneously requiring accountability.

Public discussion of city business is central to accountability. But in Los Banos, the council’s consent agenda is often loaded with actions that can be approved on a single vote with no discussion. Lewis frequently pulls items off consent to force that discussion.

The Sept. 6 consent agenda contained 15 items with expenditures totaling $2.14 million. Lewis requested five be pulled for more thorough examination.

One not discussed, however, was a change order expanding an existing paving contract by $885,760 – something the city’s Facebook page later highlighted as one of city manager Pinheiro’s accomplishments.

The original paving contract, signed in June, was for portions of five streets. The September change orders added Birch and G streets. State law requires that change orders be limited to work materially connected with the original project; Birch and G are not connected to the other five streets.

There are also limits on using change orders. The California Public Contracts Code limits them to $5,000, but there are work-arounds to that limit. The Local Agency Public Construction Act caps change orders to “generally 10 percent of the base contract,” but provides some flexibility.

Adding up the original contract and all the change orders, the city will pay United Pavement Management of Hughson $3,039,946 – an amount 48 percent higher than the original contract of $2,041,755.

Normally, a project requiring close to $1 million in paving would be sent out to bid, giving several companies an opportunity to compete. Open bidding, says the League of Cities, is necessary to “eliminate favoritism, fraud and corruption.” But no bids were requested.

There are likely explanations for the approach taken by the city: Birch and G clearly needed repaving and adding them to the existing contract allowed work to begin before the onset of an expected wet winter. But those reasons were never aired because the change order was tucked into an extensive consent agenda and passed with a single council vote.

“This council, whatever is on the agenda, they all vote for it and nobody asks any questions, other than me,” said Lewis. “I don’t know if they’re meeting behind closed doors with the city manager – I just don’t know. I’m not saying that (they’re violating the Brown Act). Maybe it’s just that whatever he wants to do, it’s OK with them.”

One Los Banos resident requested the Merced County Civil Grand Jury investigate violations of the Brown Act, California’s open-meeting law. The Grand Jury responded that it lacked jurisdiction.

“What they’re doing now, how they are fast-tracking items that should be deliberated in an open forum, this will lead to problems down the road,” said Llamas.

Los Banos resident Graciano Rubio has repeatedly come to city council meetings to demand an explanation of how the city chose recipients of federal American Rescue Plan Act funds. Rubio insists that some recipients did not qualify, and some applicants were wrongfully excluded. He accuses the council of failing to follow federal rules or even its own rules in choosing who got funding, “deliberately misleading the public” in the application process, and discriminating against some businesses while favoring others.

Rubio also accuses the city of creating confusion to avoid accountability.

“I asked for clarification after the awards went out and received three separate incorrect explanations,” said Rubio, who is a chartered financial analyst and owns two Los Banos businesses.

Rubio was provided a list of businesses selected by the city to receive ARPA funds and found Biggins Texas BBQ, owned by councilmember Ken Lambert, got $25,000. He also notes that three non-profit organizations received funding, which appears to be a violation of federal rules.

Separately, a person with knowledge of city actions and afraid of retaliation questioned the use of ARPA funding in hiring new city employees. Though some new hires are permitted to bring staff back to pre-pandemic levels under federal rules, adding staff through ARPA is not allowed.

If the city failed to follow federal guidelines, it would be in danger of having to refund some or all of the ARPA money.

Concerns about ARPA echo charges from some city employees that Pinheiro – who never worked for any government agency prior to being appointed city manager — doesn’t understand city, state or federal rules. When city employees try to correct him, staff members say Pinheiro publicly chastises them; now, many have stopped trying to correct him.

At least one long-awaited city project has virtually disappeared. A walkway/bike path linking the Los Banos campus of Merced College and the city was promised to voters during the Measure V transportation sales tax campaign in 2016. Though it was on the verge of groundbreaking, in the Sept. 6 council meeting Mayor Llanez said he considers the route unsafe. Having already insisted he would not be bound by “legacy” decisions from previous councils, he led a 4-1 vote to kill it.

The Merced County Association of Governments with the county, the college and Caltrans appear poised to provide a shortened trail from the edge of the city to the campus – as promised.

Recently, a meeting of the city’s Measure H sales-tax oversight committee, which hadn’t met in roughly two years, was hurriedly scheduled. Under the Brown Act, agendas for public meetings must be posted 72 hours in advance. But the meeting was declared an “emergency,” allowing the agenda to be posted only 24 hours prior to its start.

At the Sept. 6 council meeting, interim finance director Kuhn called the meeting “strictly informational,” failing to mention any emergency.

Opaque budget proceedings, loaded consent agendas, abandoned bike paths, unexplained handling of federal funds and circumventing Brown Act rules might seem like small things to some observers. But not to Greg Wellman.

“When I go into a job, I sweat the small stuff,” he said. “Because if you don’t sweat the small stuff, you end up with a Bell.”

Next: Afraid to say it out loud, many city staffers have no confidence in Pinheiro.

About: Journalist Mike Dunbar formerly worked for The Modesto Bee and Merced Sun-Star. Jeff Hood, a former journalist, provided research and editing assistance for this report.