The stunning vistas shown in the three photos accompanying this story all have one thing in common — at some point in the past 100 years there were movements to build highways or freeways through them.

California is considered the birthplace of the modern freeway with the opening of the Pasadena Freeway in 1938 on the Highway 110 route.

But before then the state in the 1910s through the 1930s was busy converting dirt roads between towns and trans-mountain routes that started centuries earlier as trade routes by indigenous Californians that then evolved into wagon routes.

Highway 108 with lofty Sonora Pass at 9,623 feet was one of them as was Highway 120 that reached 9,943 feet before descending Tioga Canyon.

Tioga Pass in the 1930s become the highest paved segment of the California highway system.

It holds that honor still today despite attempts by people on both sides of the Sierra — Bishop in the east and Fresno in the west — to extend Highway 168 across Piute Pass at 11,417 feet.

The idea for a southern Sierra highway crossing was born in 1919. There were repeated attempts to get the legislature on board in the 1920s before the idea died in the 1930s. The route that highway would have taken would have sliced through the John Muir Wilderness. Today it is only accessible by foot or horseback.

In the 1950s Madera County boosters set their sights on other nearby trans-Sierra routes via Mammoth Pass or the Minaret Summit.

That idea started was eventually killed by Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1972 when he persuaded the Nixon Administration to kill either route for good.

The end result today is reflected in nearly a 90-mile stretch of the Sierra crest without roads marring the adjoining Ansel Adams and John Muir wildernesses flanking both sides of the mountain range.

The stretch is bookended on the south by Highway 178’s Walker Pass at 5,250 feet and on the north by Highway 120 and Tioga Pass.

The envisioned eastern cousin to Interstate 5 was Highway 65

Closer to home, two other proposed highway/freeway routes died before they could be either started or completed.

One of them would have gone through the eastern side of both Stanislaus and San Joaquin counties.

It was part of a freeway system where a Westside Freeway that was eventually built as Interstate 5 and an Eastside Freeway would connect northern and southern California.

Just like Interstate 5 runs along the base of the Coastal foothills, Highway 65 would have run along the base of the Sierra foothills.

You would have been able to merge onto Highway 65 in Oakdale or Waterford and head north to Yuba City or south to Bakersfield.

Although the freeway was killed, two segments of the route already in place were designated as Highway 65. The northern segment runs south out of Olivehurst through Lincoln and ends in Roseville where it connects with Interstate 80.

The southern segment starts from Highway 99 near Bakersfield and ends at Highway 198 next Exeter.

The two segments represent 95 miles of the originally proposed 300-mile route.

The other was a proposal championed in 2002 by then Congressman Richard Pombo who was from Tracy.

His idea to ease traffic congestion on the Altamont Pass was to construct a freeway up Del Puerto Canyon from Patterson to San Jose where it would enter the Santa Clara Valley near the Mt. Hamilton Road.

The idea picked up support from several cities in the Northern San Joaquin Valley. Major push back from environmental groups made sure the idea was DOA before it reached consideration in the halls of state and federal power.

The idea for a 36-lane

SF Bay freeway crossing

If you’ve every driven California 1 between Carmel and San Simeon you are probably amazed that state highway engineers were able to get the road built given how it clings tightly in spots to the rugged coastlines.

Its history of landslides underscores how treacherous the terrain is.

But in 1950s state highway engineers advanced a plan to replace it with a four-lane freeway. It was proposed at the same time as the Westside and Eastside freeways in the Central Valley. The idea was dead by the early 1960s.

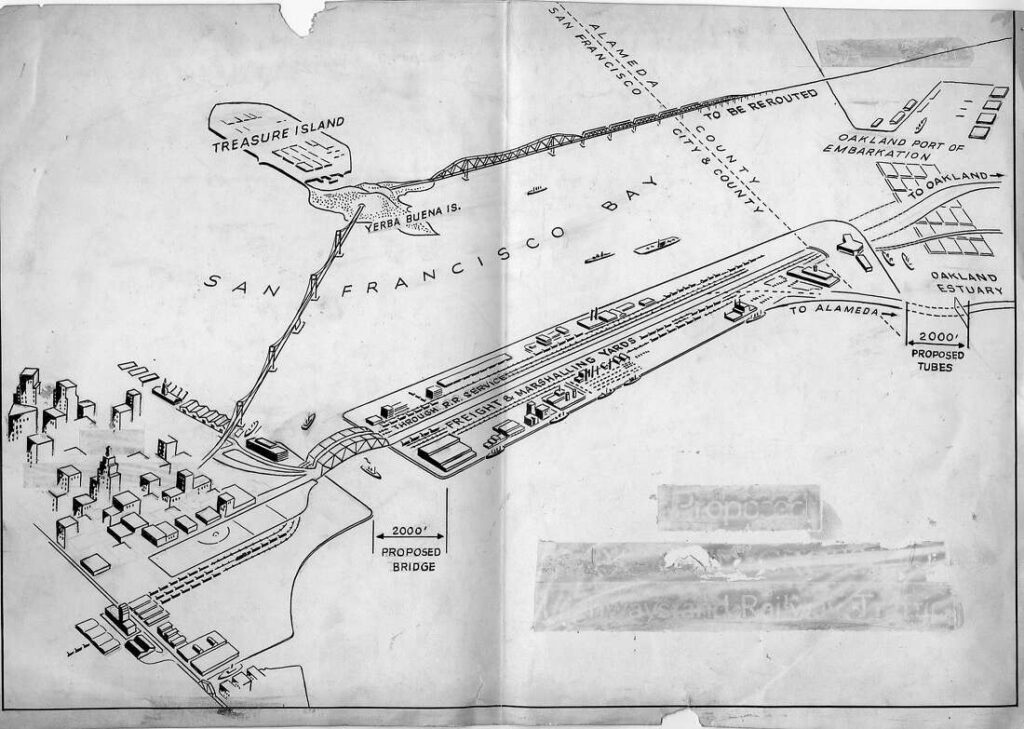

Perhaps the most stunning freeway idea that never got off the ground was for a 36-lane crossing of the San Francisco Bay south of the Bay Bridge.

In 1946 less than a decade after the Bay Bridge opened, people were grumbling about traffic. The push was on for another crossing to the south.

Several were conventional bridges.

But the one advanced by John Reber who is described as an actor who turned master planner was for a 36-lane crossing that was anything but conventional.

Reber had teamed up with Sam Francisco engineer L.H. Nishkian.

Nishkian was considered one of the top structural engineers of the day. He had a hand in designing both the Golden Gate Bridge and the SF-Oakland Bay Bridge.

The plan called for a causeway constructed on a giant earthen fill. It was to go from Alameda where it would connect to land via a tunnel before reaching the Oakland estuary to China Basin in San Francisco where the last segment would be via a 2,000-foot-long bridge.

The causeway was envisioned as nearly four-tenths of a mile wide. It called for a freeway in the middle of it 400 feet in width or enough to accommodate 36 lanes.

On both sides of the freeway, it called for 160 feet wide right-of-way for four main lines and 70 miles of sidings.

Those sidings would serve indusial areas that lined the outside of the causeway in parcels of 600 feet in depth and 1,600 feet in width.

The idea was sales and leases of industrial frontage property would have covered half of the estimated $100 million price tag.

Those tunnels on the east side would have numbered six for freeway traffic and two for railroad lines.

The idea didn’t get much traction.

It might be noted the idea of a 36-lane freeway even by modern California standards is a tad outlandish.

The mother of all freeways — the Century Freeway also known as Interstate 110 — is only 20 lanes as it passes near Los Angeles International Airport.