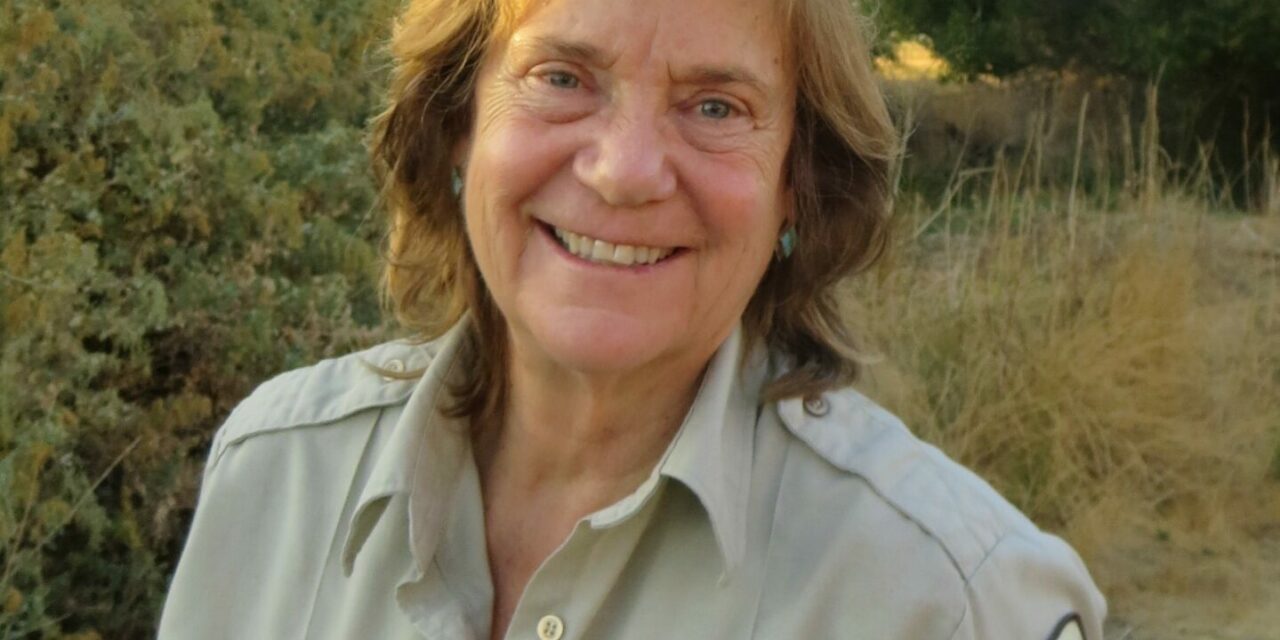

San Luis National Wildlife Refuge Complex Manager Kim Forrest is retiring after 46 years with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 22 of those years at the San Luis refuge near Los Banos.

When asked to choose which of the many projects she brought to fruition during her career she was most proud of, her answer was unexpected.

It wasn’t that she enabled construction of a multi-million dollar headquarters and visitors center at the San Luis refuge near Los Banos. Nor did she say she was most proud of winning a multi-year battle with CalTrans to build four safety turn lanes on Highway 165. And it wasn’t that she got approval from the Department of Interior to negotiate with willing sellers to purchase flood plain land along 35 river miles of the San Joaquin River.

What she considers her greatest professional accomplishment is bringing a small and secretive rabbit back from the brink of extinction and doing so by creating the largest contiguous riparian woodland restoration in California.

With funding from many federal and state grants, the Fish and Wildlife Service working with River Partners, whose mission is to bring life back to rivers by creating wildlife habitat for the benefit of people and the environment, restored about 2,500 acres of the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge to its native habitat, a habitat in which the critically endangered riparian brush rabbit could thrive.

Although thought to have gone extinct following the 1997 floods, a small population of the rabbit was found in the Sacramento-San Joaquin river delta. A portion of that population was used to launch a captive propagation project which produced about 1,500 rabbits during a 10-year period.

With professional advice about the needs of the species from California State University, Stanislaus professor Patrick Kelly, director of the Endangered Species Recovery Program, the brush rabbit population at the refuge has grown to an estimated 3,000. While still listed as an endangered species, the rabbit’s chances of survival have been greatly increased.

“The autonomy afforded to refuge managers allows for unparalleled opportunities to take conservation strides — if your stars of funding and opportunity and talent happen to be aligned,” Forrest wrote in a regional leadership post. “You just have to go after them — or create your own stars if they don’t fall into your lap. And persist.”

Forrest’s love of living things began in her childhood. A native Californian, she said she spent hours as a girl looking for horned lizards in the chapparal near her family’s home in Monterey County. She and her family also spent a month each summer exploring the back country of Yosemite.

Her connection with the natural world led to her earn a Bachelor of Science degree in wildlife biology from Utah State University. Degree in hand, her first full time job was as a clerk at Fish Springs Refuge in the western desert of Utah.

“Fish Springs is the most isolated refuge in the Fish and Wildlife Service,” she said.

Isolation notwithstanding, her clerkship there was a springboard to a promotion to assistant manager and then manager of that refuge, and was the anlage of a more than four decade career in management.

Forrest has worked at the San Luis complex for 26 of her 46 years with federal fish and wildlife, four years as manager of the Merced unit in the 1980s and as refuge complex manager since 1999. When she took over as complex manager, her and her staff’s offices were in a strip mall off Pacheco Boulevard, 10 miles from the nearest refuge.

To a great degree protecting species and habitat and conserving natural resources has to do with the political will to do so. Forrest knew that creating that will was a grassroots endeavor that could only come from the public’s appreciation of what the nearly 46,000 acres of refuge property she oversaw meant to the environment. Having a headquarters so distant from the habitat it protected and public outreach so meager as to be only wooden kiosks where pamphlets were stored to greet visitors to the refuges was not helping that endeavor.

What was needed was a headquarters building and visitors center on the refuge itself.

The opportunity to create such a structure came with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 which provided $120 billion for infrastructure projects nationwide. Some of those funds could be used to build visitor centers on wildlife refuges but it was a limited amount and there was intense competition to get projects approved for funding.

Forrest and her team at San Luis were prepared. The competition for funding between refuge projects considered size and complexity, public benefit and the proximity to population centers.

Their submission ranked fifth among the 14 projects approved nationally. It took only 11 months to plan the new headquarters and visitors center, and a year and a half to get it built on time and on budget at the San Luis refuge off Wolfsen Road near Los Banos.

The new 16,000 square-foot facility has 20 individual and two multi-user offices, three conference rooms, a large multipurpose room, and a 1,500 square-foot exhibit hall. It is the first building in the Fish and Wildlife Service to be awarded a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Platinum rating from the U.S. Green Building Council. The $10 million building opened its doors to the public in October, 2011.

Forrest was right when she assumed having a visitor’s center on the refuge would spark public interest. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Outdoor Recreation Planner Jack Sparks said about 15,000 visitors a year came through the visitors center since its opening until it had to close in 2020 due to COVID-19 restrictions. School children have benefitted especially, Sparks said. More than 50 classes per year from various grades and schools came to the refuge on field trips during the same nine-year time span.

The increase in visitation has also benefitted the economy of Los Banos since many visitors coming from the greater Bay Area spend time on the refuge and then eat at local restaurants or spend the night at local motels.

Forrest knew with increased visitation from Highway 165 to the San Luis refuge as well as the West Bear Creek unit, the hunter parking lot at the Freitas unit and access to the fire cache, there would be increased risk of accidents as cars turned off of and on to the narrow highway. She had been petitioning CalTrans to put in turn pockets to reduce that risk for almost 10 years to no avail.

Watch the face of any planner – city, county, state or otherwise – when asking the question, “What does it take to get a highway project approved through CalTrans?” What one will see are frowns, eye-rolls and sometimes tears; sighs and vague obscenities are often heard.

To promote action, she called in help from the Federal Highway Safety Administration engineers and soon the project was approved, funded and finished.

“Any one of the things she’s done for the refuge, the visitors center, bringing back an endangered species from the brink of extinction, or getting safety turn lanes built for the benefit of everyone would in itself be a legacy project,” said Sparks.

There were many other projects and programs brought about under Forrest’s watch, but for the past 22 years she was also the leader of a staff of more than 30 people, most full-time, some seasonal. According to a survey done annually by the Fish and Wildlife Service, the San Luis complex has close to the highest employee satisfaction scores for field stations in California and Nevada year after year.

“Kim is the model of a true leader,” said Sparks. “She is a great example of how to be strong and decisive while being compassionate and kind at the same time.”

Forrest’s career-long efforts to protect and conserve wildlife and habitat were not confined within national borders. Under the Department of the Interior’s International Technical Assistance Program through the State Department and USAID she travelled to Malaysia and Bangladesh to promote eco-tourism and to several countries on the African continent to help officials there prevent wildlife trafficking.

She plans to travel in retirement as well and to reconnect with old friends in Monterey. Here near Los Banos, her legacy will continue to benefit visitors to and residents of the refuges for decades to come.